Player Choice and Gameplay Styles

Player — Environment Interactions

In virtual spaces, players interact with the environment based on their psychological conditioning. In most games you usually start a game with a tutorial of sorts that is supposed to do two things:

- Teach you the game mechanics

- Condition you to associate those game mechanics to environment queues in order to establish the logic of that particular game universe.

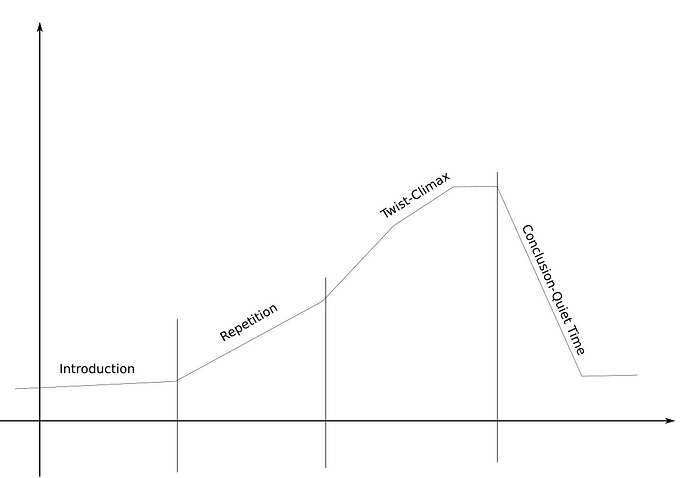

If you break down the learning curve you will get the following elements:

- Introduction — the mechanic is introduced

- The Repetition — the mechanic is repeated a few times in a similar fashion

- The Twist — The mechanic is used in a different way In order to showcase it’s behavior in relation to other mechanics.

- Conclusion- The player is rewarded a moment of quiet time

A good example of this is Half Life 2, where the concept of climbing crates is introduced, repeated and then combined with other mechanics over the course of the early hours of the game.

However there is another way of doing this that feels more organic and does not involve building extensive tutorial levels in order to showcase the game-play mechanics in a game. It’s a bit of a learn as a you go situation.

Allow me a simple analogy!

Let’s take a look at the following example:

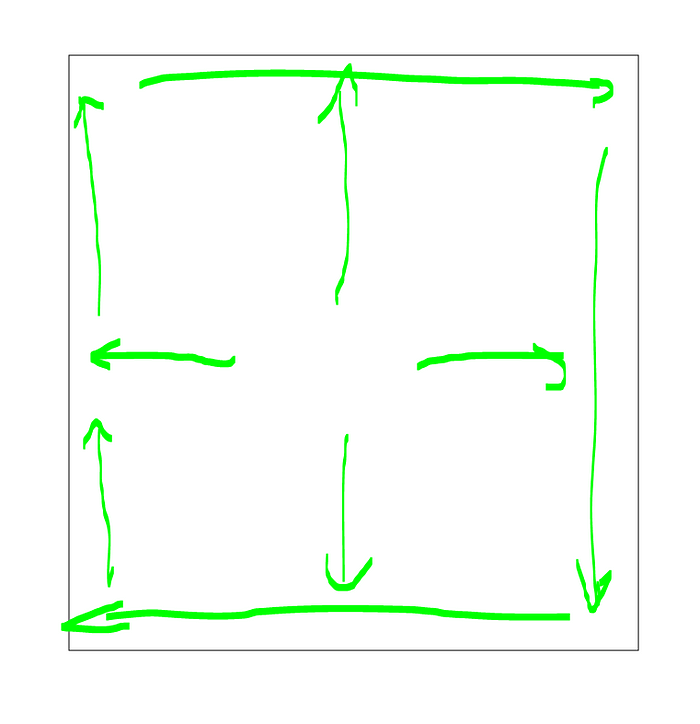

Imagine looking at a blank piece of paper:

- It’s hard to even articulate what we are looking at because there is really nothing there. It’s an empty canvas.

- If we try to add a frame to the canvas we will notice that our eyes will gently drift towards the frame.

- Even in it’s simplicity is provides contrast from the rest of the canvas, allowing us a the creators of the “picture” to control the players attention.

Adding some detail to this composition will cause the attention to drift towards that element again.

- Notice that even when not looking directly at the dot, it stands out. It contrast with the background and becomes a point of interest.

My favorite example is the “Ship at sea” trope. The size, shape and color of the ship breaks the monotony of of the sea+sky composition and the attention of the viewer will naturally shift towards the ship.

Ok… you will say! So what? I had art classes! I understand the principles of composition… why is this relevant to me as a level designer? Bare with me!

Attractors

In the previous examples we can consider the frame, the dot and ship as visual attractors. The players will pay more attention to those elements naturally.

This is why composition and visual design work, because they allow the designer to play with the viewer’s attention and to direct it to the relevant bits that actually contain either a piece of useful information or serve a functional purpose.

Affordances

An attractor that also serves a functional purpose that is consistent across the entire game will serve as an affordance for the player.

I wrote a little bit about this in my first blog available here, when I was talking about guidance and intentionality, so if you want to know more go read it there.

Examples of affordances in video games:

- Lights — because they can be broken, turned on/off, provide safety (Alan Wake)

- Switches — They turn things on and off (Every Video Game)

- Doors — They can be opened,closed,kicked some times damaging the enemies in the level (Hotline Miami, Splinter Cell)

- Cover — Characters can hide, vault over, hack (WatchDogs1,2)

- Power Generators — Control Electricity (Breakpoint, MGS5)

- Bushes — Facilitate stealth (AC: Oddisey)

- Etc.

So we have established by now that Affordances serve as gameplay enticers. The Players can use when executing their plan.

When their usefulness has been proven the players will constantly seek them out in order to incorporate them in their strategies and tactics.

Game-play Styles

If the game introduces the player to a varied amount of affordances, that has clear game-play shifting implications.

The player will drifts between game-play styles.

Examples of Affordances that Dictate Game-play Styles:

- Lights, Shadow, NPC Cone of vision, NPC Orientation, NPC Detection — Facilitate Sneaking Around

- Explosive Barrels, Gas Canisters, Rocket/Grenade Launchers, Grenadiers — Indicate a more explosive game style

- Long Ranges, Windows, Sniper Rifles, Other Snipers, Vantage Points: — Sniper Game-play Styles

- Vehicles, Roads, NPC’s in Vehicles — Lead to vehicular combat:

- Going back to the HL2 Crate Examples — Crates, metric appropriate fences, ladder — Facilitate parkour game-play styles.

Lack of affordances can also dictate what sort of game-play style you are reinforcing, however it also reduces the amount of options a player has when formulating a plan.

This leads into the concept of meaningful choice, meaning that the value of a choice in any given game-play style is given by the amount of positive feedback that a player gets when executing that choice within that particular game-play style.

Possibility Space

A possibility space is the totality of meaningful choices that the player can make at any given moment.

Players can therefor readjust their plans based on the feedback they get from the system.

Possibility space is driven by systemic interactions, Level Design flexibility and Enemy/Affordance Composition.

Player Expression

All this leads towards what we can call “Player expression”. Players are able to solve complex problems, with a limited set of tools in complex ways that are not scripted and involve systemic interactions.

Player expression is players capability of being creative with the choices that he makes.

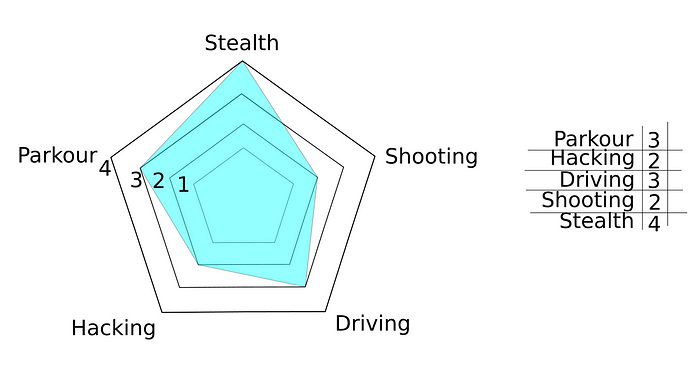

Map DNA

In large open world video games, where there are hundreds of locations and thousands of combinations between affordances, a good way of keeping things organized is to try to define a map DNA.

This is a simple diagram that is supposed to showcase and keep track of what the map is about from an affordance composition standpoint.

If we take a look at the recipe list on the right we can easily estimate what sort of affordance distribution we would like inside our map.

Based on this and other factors we can begin to plan our map.

Example:

We have a map where we would like to support:

- Parkour 3 — meaning a somewhat large amount of parkour opportunities

- Hacking 2 — meaning some hacking options but they are not the core of the experience. Will be used probably as traps and hiding collectibles, probably optional, the player will not be asked to use these extensively to finish the map

- Driving 3 — A somewhat large amount of driving, again no the crux of the map/mission but somewhat significant

- Stealth 4— Stealth options are abundant. Probably the best way to play the map but not the only one.

Note 1!

—

If you are wondering how this should be applied to your layout the answer is simple.

Try to place affordances the same way you place NPCs, however the focus should change from: Adversity to Utility.

Place them where you think the player might need them in conjunction to the micro problems you are already establishing withing your layout.

—

Note! Player Designer Handshake

An interesting concept that I came across in my work is the idea of a Player — Designer Handshake.

This implies that a level supports multiple play-styles but one of them is somewhat dominant. In our example above it is the stealth aspect.

If the player decides to take this path he is playing the map as it was intended (a nudge to designer intentionality) and will get the maximum benefit out of that gameplay style.

However that doesn’t mean that any other approach is denied, on the contrary, the player has the option to use other game-play styles as well.

—

I always try to convey the idea of Design Intentionality and in the end this is all this procedure does. It allows you to work with a good set of clearly defined intentions, as opposed to jumping straight in the editor and just building something.

I will end this blog with a quote from my former teacher and colleague Bogdan Dinca aka “Blana” :

- The focus of level design shouldn’t be on the tools, it should be on the design. Level Editors might differ from project to project, tech methodologies will differ from project to project, but Level Design Theory, careful structuring and formulation of intentions is key if you want to be a better designer. This is what differentiates a good designer from a lazy designer.

- The difference between a good and a bad level is that the good level was probably better planed and documented before it was constructed.